Author | Aubrey Kandelila Fanani

At the white crocodile cage, a sign reads, “For those expecting love, please feed this white crocodile a chicken.” Though it appears only briefly in Crocodile Tears (2024), the debut feature by Tumpal Tampubolon, the line, along with the image of the white crocodile, encapsulates the film’s essence about love.

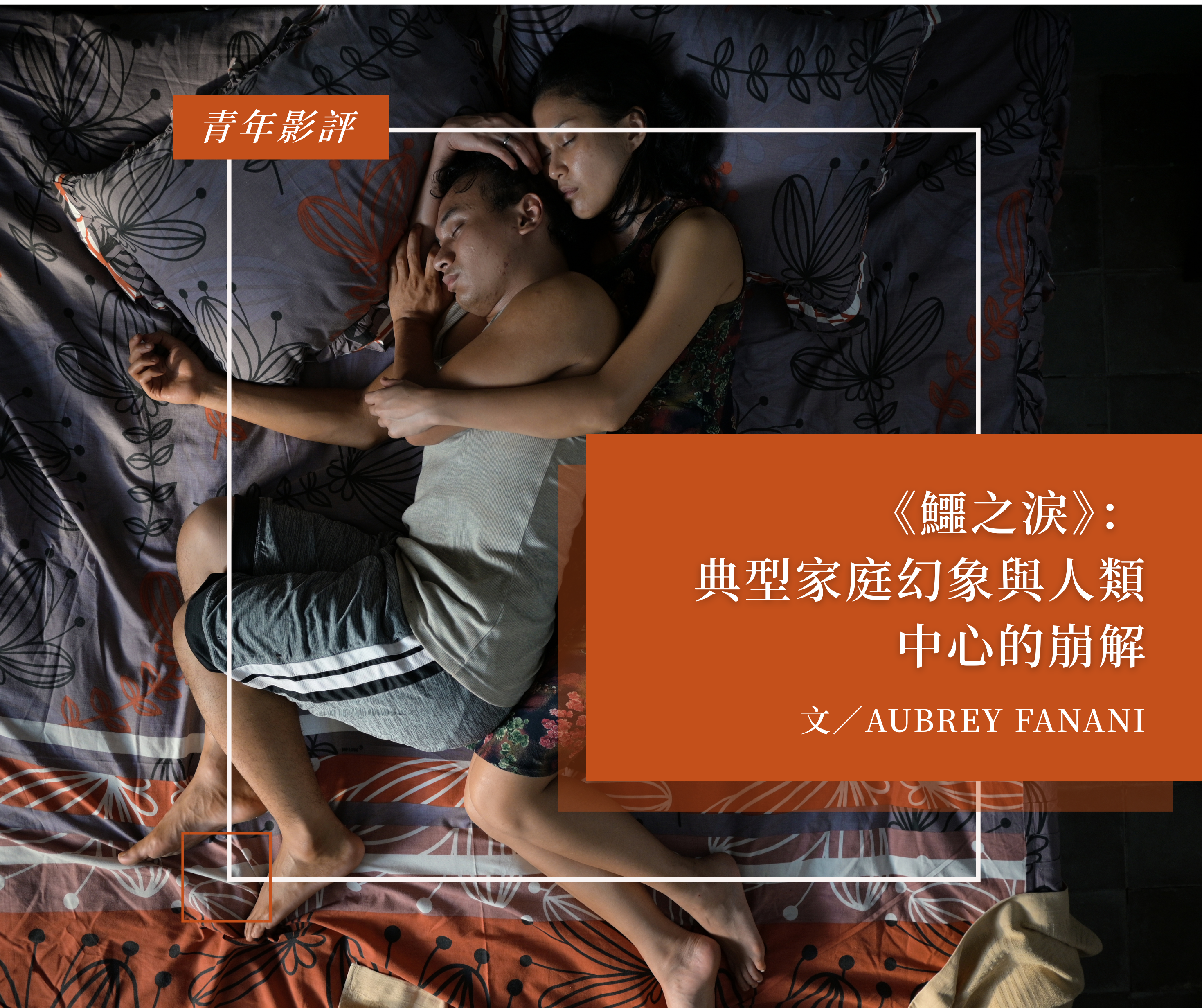

Set in the enclosed world of a crocodile park, the film takes its time to capture the intense relationship between Mama (Marissa Anita), a stern and emotionally complex mother, and her teenage son Johan (Yusuf Mahardika). Their tight-knit bond begins to unravel when Johan falls in love with Arumi (Zulfa Maharani). What seems to begin as a personal conflict quietly deepens into a meditation and illusions of love, longing, and resistance in Mama.

Though the storyline might be simple, the film's complexity lies in the characters. With minimal dialogue, the dynamic between controlling Mama and obedient Johan feels natural and engaging. The chemistry and emotional timing between the actors bring the scenes to life.

Marissa Anita, who played Mama, brings a stunning emotional range, portraying a quiet, vulnerable, loving, and caring mother, to fierce intensity. She shifts her gesture from calm and assertive with her son to tense and confrontational when facing Arumi. Yusuf Mahardika, who played Johan, portrays the typical Mama's boy. His eyes were timid, and he always lowered his gaze. Obedient in practice by consistently saying yes to Mama. However, when he meets Arumi, he begins to change while still maintaining his obedience to Mama.

What we must appreciate is the director's attempt to wrap the film not in the conventional family drama or horror story. Instead, he tried to bend and mix some genre elements in the film. Even Tampubolon does not want to categorize the film into a certain genre, but I might say this film is like a magical realism, which combines drama, thriller, and myth, in a realistic tone.

Through this approach, the director has blurred time and space, the boundaries between the dream, the hallucination, fear, and reality. Through this blurry time and space, the film could capture the deep trauma that Mama and Johan experienced. Although the narrator seems unreliable, this may reflect the struggles faced by individuals with mental health issues, who often find it difficult to distinguish between hallucination and reality, as well as between repression, fear, and dreams.

Moreover, Crocodile Tears extends beyond domestic drama. It probes the societal ideal of the nuclear family and explores how love can be shaped, distorted, or even weaponized by tradition and expectation. The film also critiques anthropocentrism by examining the relationship between humans and nonhumans.

Beyond the Nuclear Family

By placing the sacred white crocodile at the center of its mythic and symbolic framework, Crocodile Tears offers a radical critique of the nuclear family and the social structures that support it. In the film, Mama calls the white crocodile her husband, forming a family unit that includes herself, her son Johan, and the animal. This unconventional arrangement disrupts the dominant ideal of family in Indonesia, which has long been institutionalized and reinforced through law, media, and public discourse.

In 1988, the Indonesian Ministry of Health defined the family as the smallest unit of society, consisting of a head of the family and individuals living together under one roof in a state of interdependence. In this structure, the father is positioned as the head of the household and is responsible for engaging in the public sphere, while the mother is tasked with domestic responsibilities—raising children, managing household needs, and maintaining emotional care.

Children, in turn, are expected to be obedient and passive, with limited agency or freedom. This traditional model has been consistently portrayed in educational curricula and reinforced by television series, public campaigns, and advertisements that normalize the roles of each family member.

Johan embodies the illusion of love and societal expectations of obedient, passive children. When he defies his mother, he experiences intense emotional outbursts. He sees Mama screaming, crying, and possessed. Although these moments are symbolic, they reflect the psychological terror that social norms impose. The more Johan attempts to distance himself from his mother or disobeys her, the more the situation escalates. This illustrates how disobedience is punished with feelings of guilt and fear.

However, this narrow definition of family no longer reflects the diverse realities of many Indonesian families. It excludes single-parent households, families without children, women as heads of households or breadwinners, and even emotional bonds with non-human beings.

In this context, Mama's relationship with the crocodile becomes an act of dissent against the rigid expectations of family life. Her declaration of the crocodile as her husband is not just surreal. It is a subversive gesture that both mocks and mourns the unfulfilled promise of the traditional family.

Her desire to maintain the image of a complete household—despite the absence of a human father—can be understood through the Lacanian concept of desire, which arises from lack. But whose desire? Apparently, it is not Mama’s desire but the social and state desire to expect the standards and morals of an ideal nuclear family. The crocodile then becomes a projection of her longing to meet the ideal she has been taught to want but cannot attain.

The film further complicates this critique through its treatment of the absent father figure. The father never appears on screen, and his presence exists only through rumor and memory. The villagers whisper that Mama killed him; Johan believes he simply left when he was young. Mama herself remains silent on the matter. This ambiguity turns the father into a myth—an idea rather than a person. His absence disrupts the patriarchal order, calling into question the necessity of a father figure in defining family, authority, and identity. The myth of the father, constructed through stories rather than fact, mirrors the social myth of the nuclear family, a structure that often fails to reflect lived experiences.

Mama's role as both mother and provider, and her symbolic replacement of the father with a crocodile, dismantles the conventional family dynamic and reimagines it as fluid, unstable, and shaped by need rather than norm. The film challenges the gendered division of labor and care, critiques the deep-seated expectation that women fulfill both emotional and structural needs within the home, and redefines what constitutes family beyond biology or legality.

The critiques of anthropocentrism

Tampubolon weaves mythology, folk tales, and grounded realism to create a layered narrative that explores not just human relationships but also the spiritual and cultural forces surrounding them. Central to this is the crocodile—sacred in some Indonesian traditions—which becomes a symbol for examining the human-nonhuman dynamic.

While the film focuses on human love, it also critiques anthropocentrism—the belief in human superiority over nature. Historically, humans have subdued the natural world, domesticating animals for labor or consumption. In Crocodile Tears, the once-wild crocodiles are confined to a pool, fed by humans, and reduced to both workers and spectacles for villagers.

What makes the film truly engaging is that the crocodile park isn’t just a backdrop or a setting palace. It’s a living, breathing part of the story. The characters don’t merely exist in the setting; they truly inhabit it. The presence of the crocodiles permeates the film, silent yet symbolic. Although they don’t speak, their presence carries significant weight. We can feel how eerie this crocodile is in the opening scene when Johan hears his mother crying and screaming for him. As he runs towards her, the crocodile's eyes light up, following the direction he runs, as if it is watching him. In another scene, we see Johan casually carrying a young crocodile, as if this crocodile is tame and not dangerous.

Yet the film questions whether they are truly tamed. Instead, the crocodiles slowly reclaim power, subtly dominating the human characters. Isolated within the park, Mama and Johan are physically and psychologically shaped by their environment, smelling of fish, mimicking crocodilian gestures, and haunted by reptilian nightmares. The conquerors become the conquered.

In this case, Mama seems the most affected, her behavior turns like a crocodile. She is territorial, protective of her young, and aggressive when she feels threatened. She perceives Arumi as a predator who poses a threat to her son. This is evident in the scene where Mama becomes upset upon learning that Johan returned late after being intimate with Arumi. The following morning, she bathes her child, pouring water over both him and herself. In her desperation, Mama claims that Arumi has tainted her child and their family.

Through this inversion, the film highlights the fragile boundary between humans and nonhumans, offering a sharp critique of domination and control in our relationship with nature.

Visually and thematically, Crocodile Tears is a bold debut that stands out for its restraint and quiet intensity. Through its thrilling storytelling and symbolic imagery, the film offers a rich, unsettling meditation on love, not as a simple emotion, but as a complex, often contradictory force shaped by trauma, desire, fear, and belief.