文/Aubrey Kandelila Fanani

在白鱷籠前,一塊牌子寫著:「若你期待愛情,請餵給這隻白鱷魚一隻雞。」這句話在《鱷之淚》(2024)中只短暫出現一瞬,卻連同白鱷魚的意象,一舉道出本片對愛的詮釋。

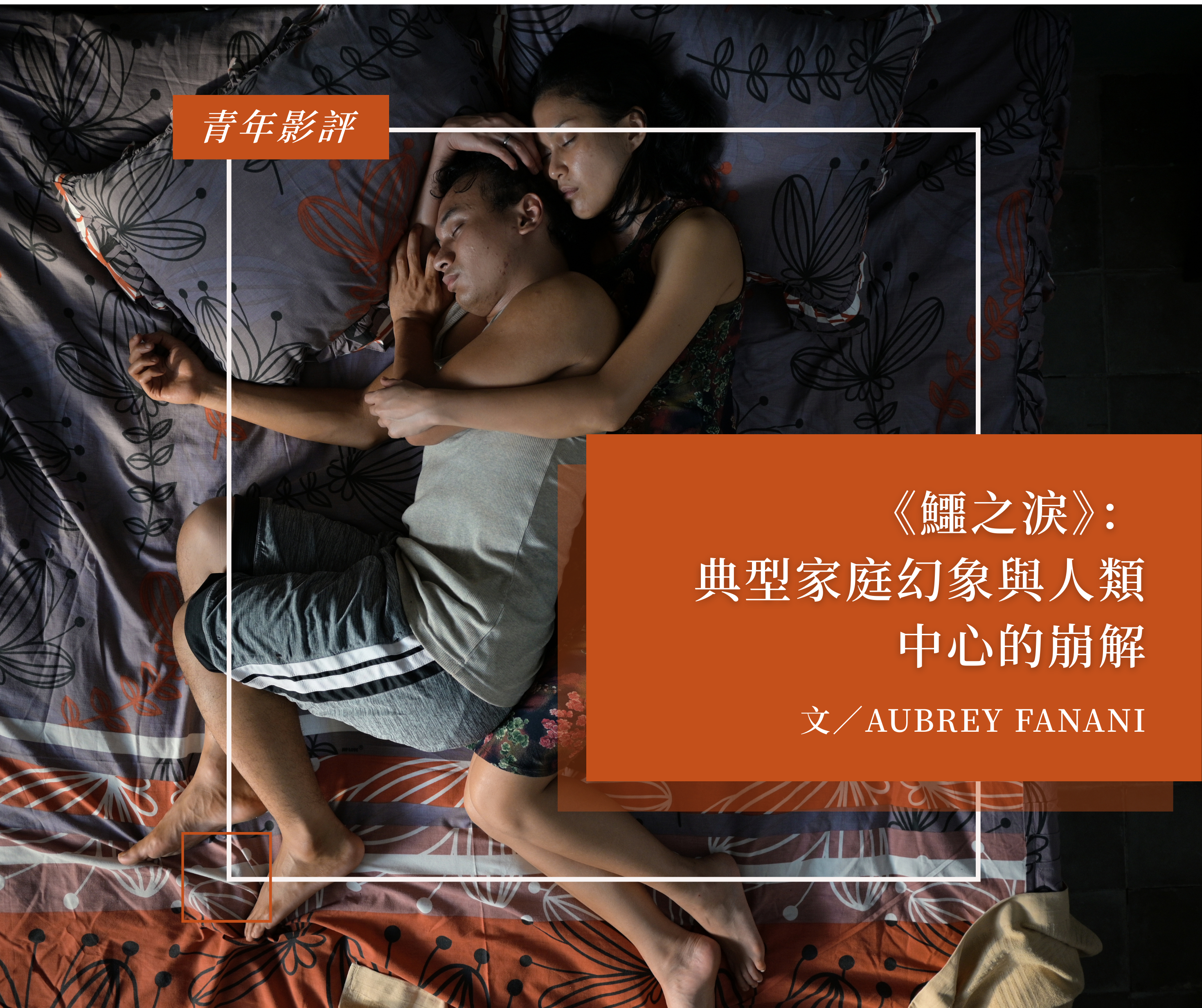

本片為印尼導演頓帕・湯普波藍(Tumpal Tampubolon)的長片處女作,故事背景設定在一處鱷魚公園,鏡頭細膩捕捉母親(Marissa Anita 飾)與青少年兒子約翰(Yusuf Mahardika飾)之間既緊密又複雜的關係。當約翰愛上女孩阿茹米(Zulfa Maharani 飾)時,原本穩定的親子關係悄然裂解,一場看似私人衝突,也逐漸揭露母親內心對愛、渴望與控制的幻覺與掙扎。

儘管情節簡潔,但人物描寫極具層次。全片對白極少,卻讓母親的控制與約翰的順從展現得真切自然。兩位演員的化學反應與情感節奏,為角色注入生命。

飾演母親的 Marissa Anita 展現出驚人的情緒張力,時而沉穩克制、溫柔呵護,時而強勢激烈。她在兒子面前冷靜堅定,面對阿茹米時則顯得緊繃易怒。約翰一開始像是典型的「媽寶」,目光怯懦、總是低頭,順從地對母親言聽計從,直到與阿茹米的邂逅,才開始顯現改變,但依然難以擺脫對母親的服從。

值得稱許的是導演不將本片歸類為單純的家庭劇或恐怖片,而是巧妙地揉合了不同類型元素。他本人甚至不願將電影歸屬任何類型,我們或可稱其為一種「魔幻寫實」:在現實基調中混融戲劇、驚悚與神話。

透過此種敘事策略,導演模糊了夢境、幻覺、恐懼與現實之間的界線,展現媽媽與約翰內心深處未曾言說的創傷。儘管敘事視角可能顯得不可靠,卻正好對應心理疾病患者難以分辨真實與幻象、壓抑與恐懼、夢境與現實的處境。

超越核心家庭的想像

白鱷魚不僅是神話象徵,更成為本片對核心家庭(小家庭)與其背後社會結構的激進批判。在故事中,母親稱白鱷魚為她的丈夫,組成了一個非典型的家庭:母親、兒子與鱷魚。這種安排衝擊印尼長年透過法律、媒體與公共論述所建構的家庭理想。

印尼衛生部曾在1988年定義家庭為「社會中最小的單位,由一家之主與共居並彼此依賴的成員組成」,父親掌管外務、母親負責家務與育兒,孩子則須順從聽話。這種模式不僅深入課綱,也廣泛滲透於電視劇、公眾宣導與廣告中。

約翰體現了這種核心家庭對「乖小孩」的愛與期待。當他首次違逆母親時,迎來的是媽媽歇斯底里的崩潰、哭喊與如著魔般的表現。這些象徵性的片段,實則揭露社會規訓所施加的心理恐懼:違逆便是錯,違逆會帶來罪惡感與災難。

然而,這種定義早已無法涵蓋當今印尼家庭的多樣樣貌:單親家庭、無子女家庭、女性擔任家中經濟支柱的家庭,甚至與非人動物之間的情感聯繫。

在此脈絡下,媽媽與鱷魚之間的關係便是一種抵抗。她宣稱鱷魚為夫,既荒誕又悲傷,是對傳統家庭理想無法實現的控訴與戲謔。拉岡曾提出「欲望源自匱乏」,但媽媽的欲望,顯然並非她個人的選擇,而是社會與國家強加的規範期待。鱷魚於是成了她對理想家庭的投射,對她無法實現卻又被迫渴望的形象之寄託。

片中更進一步地讓「父親」角色完全缺席,只存於回憶與傳言之中——有人說他被媽媽殺了、也有人說他早早離家。這層不確定性,使「父」成為一種神話——一種被虛構出來、從未具象存在的秩序象徵,也對「家需要父親」的社會建構提出質疑。

當媽媽同時擔任母親與家庭支柱,又以鱷魚取代丈夫的象徵,便推翻了性別分工與家庭角色的傳統定義。她不再只是承擔情感照顧,更被迫扛起整個結構,而電影則質疑:家庭的存在與價值,難道只能建立在生物學與法律之上?

對人類中心主義的批判

導演透過神話、傳說與寫實交織的敘事,關照的不僅是人與人之間的關係,更是人與自然、人與非人生命體之間的情感與權力結構。

鱷魚在印尼某些文化中被視為神聖的象徵,本片則將其置於人類與非人類關係的鏡像位置,對人類中心主義(anthropocentrism)提出質疑——即認為人類高於自然、自然是為人所用的信念。

在電影中,曾經野性的鱷魚被囚禁、圈養,淪為村民觀賞與餵食的對象——牠們成了勞動者、娛樂者,卻不再是自主的生命。

而導演最令人驚艷之處,在於這些鱷魚並非只是背景裝飾,而是影像與敘事中的主體角色。從片頭那場驚悚戲開始,媽媽的哭喊與鱷魚注視約翰奔跑的眼神交織出一種超越人類的感知網絡。另一場戲中,約翰抱著幼鱷走動,彷彿牠已不具危險,飼主與鱷魚間的界線早已模糊。

但,牠們真的被馴服了嗎?電影以極細緻的鋪陳逐漸揭示:鱷魚開始反過來控制人類角色。被隔絕於鱷魚公園內的媽媽與約翰,身體與精神逐漸被鱷魚化——他們身上有魚腥味、行為模仿鱷魚、夢中被鱷魚纏繞,從征服者變成被征服者。

其中變化最劇烈的是媽媽,她愈來愈像一隻鱷魚——領地意識強烈、為護子而攻擊。她將阿茹米視為掠食者,是會奪走兒子的威脅者。當約翰與阿茹米親密後返家,她暴怒並清晨為兒子沐浴,也為自己澆水,口中責罵阿茹米「弄髒了」他們的家庭。

這種主客體顛倒的安排,正凸顯人與自然間的脆弱邊界——「征服」的背後,其實是共構與反噬的關係。

《鱷魚之淚》是一部節制而深刻的電影處女作。它以柔和而陰鬱的語氣、緊湊的敘事與象徵影像,帶領觀眾深入思索「愛」——那既溫柔又扭曲、既渴望又壓抑的複雜情感。它挑戰我們對家庭、情慾、人類與自然之間秩序的既定認知,也在白鱷閃爍的目光下,反問我們:究竟什麼才是真正的親密與愛?

——————————

原文英文

Crocodile Tears: Desire of the Nuclear Family and Critics of Anthropocentrism

By Aubrey Kandelila Fanani

At the white crocodile cage, a sign reads, “For those expecting love, please feed this white crocodile a chicken.” Though it appears only briefly in Crocodile Tears (2024), the debut feature by Tumpal Tampubolon, the line, along with the image of the white crocodile, encapsulates the film’s essence about love.

Set in the enclosed world of a crocodile park, the film takes its time to capture the intense relationship between Mama (Marissa Anita), a stern and emotionally complex mother, and her teenage son Johan (Yusuf Mahardika). Their tight-knit bond begins to unravel when Johan falls in love with Arumi (Zulfa Maharani). What seems to begin as a personal conflict quietly deepens into a meditation and illusions of love, longing, and resistance in Mama.

Though the storyline might be simple, the film's complexity lies in the characters. With minimal dialogue, the dynamic between controlling Mama and obedient Johan feels natural and engaging. The chemistry and emotional timing between the actors bring the scenes to life.

Marissa Anita, who played Mama, brings a stunning emotional range, portraying a quiet, vulnerable, loving, and caring mother, to fierce intensity. She shifts her gesture from calm and assertive with her son to tense and confrontational when facing Arumi. Yusuf Mahardika, who played Johan, portrays the typical Mama's boy. His eyes were timid, and he always lowered his gaze. Obedient in practice by consistently saying yes to Mama. However, when he meets Arumi, he begins to change while still maintaining his obedience to Mama.

What we must appreciate is the director's attempt to wrap the film not in the conventional family drama or horror story. Instead, he tried to bend and mix some genre elements in the film. Even Tampubolon does not want to categorize the film into a certain genre, but I might say this film is like a magical realism, which combines drama, thriller, and myth, in a realistic tone.

Through this approach, the director has blurred time and space, the boundaries between the dream, the hallucination, fear, and reality. Through this blurry time and space, the film could capture the deep trauma that Mama and Johan experienced. Although the narrator seems unreliable, this may reflect the struggles faced by individuals with mental health issues, who often find it difficult to distinguish between hallucination and reality, as well as between repression, fear, and dreams.

Moreover, Crocodile Tears extends beyond domestic drama. It probes the societal ideal of the nuclear family and explores how love can be shaped, distorted, or even weaponized by tradition and expectation. The film also critiques anthropocentrism by examining the relationship between humans and nonhumans.

Beyond the Nuclear Family

By placing the sacred white crocodile at the center of its mythic and symbolic framework, Crocodile Tears offers a radical critique of the nuclear family and the social structures that support it. In the film, Mama calls the white crocodile her husband, forming a family unit that includes herself, her son Johan, and the animal. This unconventional arrangement disrupts the dominant ideal of family in Indonesia, which has long been institutionalized and reinforced through law, media, and public discourse.

In 1988, the Indonesian Ministry of Health defined the family as the smallest unit of society, consisting of a head of the family and individuals living together under one roof in a state of interdependence. In this structure, the father is positioned as the head of the household and is responsible for engaging in the public sphere, while the mother is tasked with domestic responsibilities—raising children, managing household needs, and maintaining emotional care.

Children, in turn, are expected to be obedient and passive, with limited agency or freedom. This traditional model has been consistently portrayed in educational curricula and reinforced by television series, public campaigns, and advertisements that normalize the roles of each family member.

Johan embodies the illusion of love and societal expectations of obedient, passive children. When he defies his mother, he experiences intense emotional outbursts. He sees Mama screaming, crying, and possessed. Although these moments are symbolic, they reflect the psychological terror that social norms impose. The more Johan attempts to distance himself from his mother or disobeys her, the more the situation escalates. This illustrates how disobedience is punished with feelings of guilt and fear.

However, this narrow definition of family no longer reflects the diverse realities of many Indonesian families. It excludes single-parent households, families without children, women as heads of households or breadwinners, and even emotional bonds with non-human beings.

In this context, Mama's relationship with the crocodile becomes an act of dissent against the rigid expectations of family life. Her declaration of the crocodile as her husband is not just surreal. It is a subversive gesture that both mocks and mourns the unfulfilled promise of the traditional family.

Her desire to maintain the image of a complete household—despite the absence of a human father—can be understood through the Lacanian concept of desire, which arises from lack. But whose desire? Apparently, it is not Mama’s desire but the social and state desire to expect the standards and morals of an ideal nuclear family. The crocodile then becomes a projection of her longing to meet the ideal she has been taught to want but cannot attain.

The film further complicates this critique through its treatment of the absent father figure. The father never appears on screen, and his presence exists only through rumor and memory. The villagers whisper that Mama killed him; Johan believes he simply left when he was young. Mama herself remains silent on the matter. This ambiguity turns the father into a myth—an idea rather than a person. His absence disrupts the patriarchal order, calling into question the necessity of a father figure in defining family, authority, and identity. The myth of the father, constructed through stories rather than fact, mirrors the social myth of the nuclear family, a structure that often fails to reflect lived experiences.

Mama's role as both mother and provider, and her symbolic replacement of the father with a crocodile, dismantles the conventional family dynamic and reimagines it as fluid, unstable, and shaped by need rather than norm. The film challenges the gendered division of labor and care, critiques the deep-seated expectation that women fulfill both emotional and structural needs within the home, and redefines what constitutes family beyond biology or legality.

The critiques of anthropocentrism

Tampubolon weaves mythology, folk tales, and grounded realism to create a layered narrative that explores not just human relationships but also the spiritual and cultural forces surrounding them. Central to this is the crocodile—sacred in some Indonesian traditions—which becomes a symbol for examining the human-nonhuman dynamic.

While the film focuses on human love, it also critiques anthropocentrism—the belief in human superiority over nature. Historically, humans have subdued the natural world, domesticating animals for labor or consumption. In Crocodile Tears, the once-wild crocodiles are confined to a pool, fed by humans, and reduced to both workers and spectacles for villagers.

What makes the film truly engaging is that the crocodile park isn’t just a backdrop or a setting palace. It’s a living, breathing part of the story. The characters don’t merely exist in the setting; they truly inhabit it. The presence of the crocodiles permeates the film, silent yet symbolic. Although they don’t speak, their presence carries significant weight. We can feel how eerie this crocodile is in the opening scene when Johan hears his mother crying and screaming for him. As he runs towards her, the crocodile's eyes light up, following the direction he runs, as if it is watching him. In another scene, we see Johan casually carrying a young crocodile, as if this crocodile is tame and not dangerous.

Yet the film questions whether they are truly tamed. Instead, the crocodiles slowly reclaim power, subtly dominating the human characters. Isolated within the park, Mama and Johan are physically and psychologically shaped by their environment, smelling of fish, mimicking crocodilian gestures, and haunted by reptilian nightmares. The conquerors become the conquered.

In this case, Mama seems the most affected, her behavior turns like a crocodile. She is territorial, protective of her young, and aggressive when she feels threatened. She perceives Arumi as a predator who poses a threat to her son. This is evident in the scene where Mama becomes upset upon learning that Johan returned late after being intimate with Arumi. The following morning, she bathes her child, pouring water over both him and herself. In her desperation, Mama claims that Arumi has tainted her child and their family.

Through this inversion, the film highlights the fragile boundary between humans and nonhumans, offering a sharp critique of domination and control in our relationship with nature.

Visually and thematically, Crocodile Tears is a bold debut that stands out for its restraint and quiet intensity. Through its thrilling storytelling and symbolic imagery, the film offers a rich, unsettling meditation on love, not as a simple emotion, but as a complex, often contradictory force shaped by trauma, desire, fear, and belief.